Moving the Needle on Local Ownership in USAID/Vietnam Programming

Development requires local ownership for long-term success and sustainability. We all know this, and if we’re being honest, we also all know it is a struggle.

We wanted to help USAID and partners push a little bit more to get to greater local ownership; so much is already happening, but can we make even more progress?

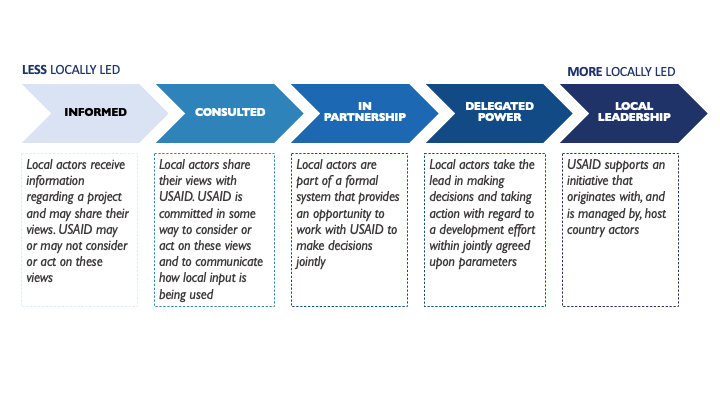

We started from the locally-led development framework put forward by USAID’s Local, Faith, and Transformative Partnerships Hub (found here) and asked ourselves: what would more locally-led development look like in the Vietnam context? Where can we improve practices, even if only slightly, to move closer to the right side of this spectrum?

As a result, we created this “localized” version of the spectrum above with specific ideas for how USAID/Vietnam and its implementing partners could get closer to local leadership during design, procurement, and implementation.

Here are some of our examples of this localization in action during these phases of the Program Cycle.

Design

Over the last few years, USAID/Vietnam has pushed for greater local ownership in the design process. In the Vietnam context, any donor-funded program should have project approval from the Government of Vietnam (GVN) as required by Vietnamese law. Project approval formally demonstrates GVN’s commitment and partnership to carry out the objectives of the program. However, it can be a cumbersome process with multiple government agencies involved, the most important of which is known as the managing agency that is considered the primary government counterpart for the program. A 2021 USAID/Vietnam internal review found that over half of USAID's approved projects took over one year to obtain project approval. Of those, 34% took over two years to obtain project approval. The average project lasts about five years; as a result, roughly 20%-40% of the implementation period may be spent seeking project approval. Typically, USAID's implementing partners are limited in their ability to implement without project approval, representing significant inefficiency in delivering development results. Equally important, a lack of project approval also means that USAID and its implementing partners don’t have buy-in from the managing agency which can lead to significant issues during implementation.

In response to this challenge and based on learning from its Government Project Approval Study carried out by USAID Learns, USAID/Vietnam adjusted its internal design procedures (the Mission Order on Project and Activity design) to move towards greater local ownership. These changes included: (1) requiring identification of the managing agency during the design process; (2) engaging the managing agency more intentionally during the design phase; and, in some cases, (3) signing Memorandums of Understanding or Limited Scope Grant Agreements (LSGA) to agree on shared outcomes and objectives. This higher level of collaboration then often feeds into design meetings between USAID and the managing agency to agree on target locations and key interventions or approaches, setting the implementing partner up for potentially quicker project approval post-award.

USAID/Vietnam also engages non-governmental local stakeholders during the design process. For example, using the Theory of Change Workbook, USAID Learns helped facilitate collaboration with local experts and well-respected environmental protection organizations that informed USAID’s Vietnam Action Against Plastic Pollution solicitation.

Procurement

USAID/Vietnam also adjusted its procurement processes, particularly for cooperative agreements to actively collaborate with the managing agency and relevant local stakeholders. This process, known as the Strategic Alignment Validate Exercise (or SAVE), is intended to save time seeking project approval after award. SAVEs can take many forms but the end result is buy-in from the managing agency on the scope of the new activity. Even in cases where the managing agency is actively involved in the design, they can also use the SAVE to get other government agencies on board, enabling intragovernmental collaboration on the Vietnam side. Under Office of Acquisition and Assistance (OAA) leadership and in collaboration with technical offices, USAID Learns has facilitated numerous SAVEs and documented the process and available resources for USAID staff in the SAVE roadmap. These changes were also shared in our CLA case competition entry selected as a finalist in 2021.

Implementation

During implementation, implementing partners work with the managing agency to finalize the project approval document which reflects a shared vision and plan for the program. In many cases, there is a joint management structure where the Chief of Party has a counterpart on the GVN side to jointly manage implementation. Implementing partners are encouraged by USAID to pause and reflect annually (many have required annual reflections in their awards) with government counterparts to inform work planning. In 2021, USAID/Vietnam, via USAID Learns with speakers from Winrock International and PATH, hosted a webinar for partners on collaborative work planning with government counterparts to share experiences and develop “do’s” and “don’ts” that can help other partners more intentionally collaborative with GVN counterparts.

Within this context, USAID Learns supported USAID/Vietnam on the design of the Reducing Pollution Activity, now implemented by Winrock International, that emphasized local ownership throughout. The activity follows the collective impact model whereby local stakeholders come together under a common agenda to reduce environmental pollution in an area of importance to them. The activity lays out the broad parameters, such as reducing plastic pollution, but local organizations and their government counterparts develop proposals on their own that identify the what, how, and where based on local needs and priorities. Initiatives are then managed by local organizations who act as “backbones” facilitating collaboration among local stakeholders from the government, private sector, and civil society to achieve results.

Research and evaluation activities during implementation are also an opportunity for greater local ownership. USAID Learns carries out the majority of research and evaluations required by USAID/Vietnam. In one case, the managing agency requested the evaluation and was in the driver’s seat during the scoping process. In other cases, local stakeholders are involved in scoping and defining what matters to them; for example, in a recent sustainability review of IMPACT-MED, USAID Learns engaged local universities in defining what sustainability meant to them to inform the rest of the research. And in almost all cases, we engage local stakeholders in jointly developing recommendations based on findings so that those recommendations are locally-owned. My colleague, Phuong Pham (USAID Learns’ former Research Director) documented localization approaches for the American Evaluation Association here, and we co-hosted a webinar for USAID/Vietnam staff and partners on participatory research approaches in collaboration with USAID’s Local, Faith, and Transformative Partnerships Hub.

USAID implementing partners are also doing this directly with local stakeholders during implementation. For example, Arizona State University’s BUILD-IT program strengthens higher education institutions in Vietnam, enabling them to improve education quality and achieve international accreditations, as well as foster university-industry collaborations. After being trained in the Most Significant Change methodology by USAID/Vietnam via USAID Learns, BUILD-IT implemented the approach and asked its program beneficiaries what they perceived to be the most significant changes resulting from the program. From this learning, BUILD-IT enhanced its capability to determine how, where, and what to scale, reaching more academic programs in target universities.

Localization - like most aspects of development work - looks different based on location. In the Vietnam case, with a receptive, CLA-oriented Mission and local requirements, we have managed to move closer to the right side of the locally-led development spectrum. And, of course, even more can be done.

What would more local ownership look like in your context? Where can you improve practices, even if only slightly, to move closer to locally-led development?